Previously in part IV

…In the years that followed, the Diocese tacitly conceded defeat to whatever malevolence had wrested St Cornelius from its bosom. A church was its congregation, and congregation was there none; St Cornelius was deconsecrated. As the Bishop snuffed the last ceremonial candle, such strictures of holiness as there might have been fell away, and in that same instant, Mungo awoke with a great groan. The thick blanket of laudanum within his mind was shredded and Speighthart’s peals of victorious, gloating mirth echoed loud…For the rest of your natural and most wretched life!…

If you wish to start at the beginning, which is highly recommended Click Here,

A new century begins, but in Never Clevehaven, things change hardly at all. Mephistopheles complains to the wind of her ancient joints with creaks and groans, or perhaps she utters vainly But you misunderstand… I am a lady! A speckle of wanton red berries fleck her boughs with toxic promises, but the gates of the churchyard are rusted closed; the walls are high and visitors few. Beneath her trunk, hollow and split by the millennia, beneath her layered skirt of needles, her roots form gently, slowly, their embrace around the Reverend’s blighting bones. She waits. She is nearly three thousand years old but at once ageless, timeless. She will kill again.

This new century is one of new invention, of new wars; new politics, death, scandal and music and above all speed. Everything done at speed; faster and faster still, the machines of commerce and destruction churn. Changes spread out into the world, disfiguring it like tear stains on a delicate watercolour; like the salt bloom on plasterwork as ash filled rain soaks damp through the walls.

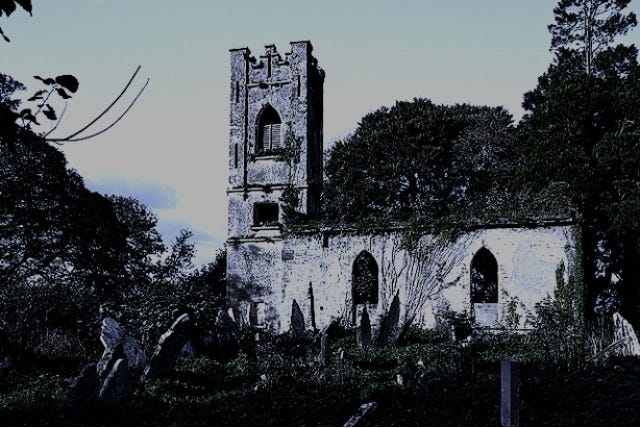

And change comes even to Nether Clevehaven and the villages that lie around it. But, here, the march of time plays out such that, if one were to have sped it up, it would appear as if the town tip-toed itself away from the church, hoping not to wake it. St Cornelius stands isolated, with only the empty vicarage for company. A fire destroys the nearby bakery and fatally wounds the adjoining post office. They are not rebuilt.

Churchwynd, now an untraveled lane, is consumed by moss and Jack-by-the-hedge, its avenue of trees spread their arms towards each other and bar the way forward. Uncut grass drowns the graves in a sea of green, and only the wingtips of granite angels and roundels of Celtic crosses emerge from the depths. Much like the saint himself, St. Cornelius is forgotten. Deconsecrated, it is relegated to nothing but a line within a dust-gathering terrier of the regional land holdings of the Church. It becomes but a name and a valuation; and a low one at that.

What of the curse? The generation most affected by it disappear into the past. They die, as decreed, at the end of lives blighted by miserable fortune. Their tales of woe become family histories only, and laughed at as much as bemoaned. The victims become poor Great Aunt Maude, or mad Grandfather Jack, recalled for their eccentricities. Time, the search for work, the Great War and the Spanish Flu take the first hand witnesses, but the curse lingers on in the ground. From time to time, by twist of genealogy and fate, it manifests…

The war-time drive for gun metal saw one lusty lad caught rudely on the spike of railings as he cut them from the churchyard wall. His grandfather, Jack Slatnapper one handed and peg toothed, screeched “The Curse! It be the Curse still upon us!” as he banged his ale tankard down. Misfortune indeed for the grandson, but perhaps a good thing for the Slatnapper line not to continue and tempt foul fate?

Ms. Philippa Flux bore her child within the poorhouse, but gave him up for gin and sixpence to a better life, she told herself; or, at least, a longer one. Grown lean on hunger, the hardships of his life were as a whetstone to his instincts, but alas, it was to crime that he turned his intelligences, and, in particular, to the burglary of great houses. His angular frame and slight stature that starvation had bestowed upon him were gifts to his nocturnal insinuations through sash windows and the assent of gutter pipes.

A dead lurker, a skillful, dipper a blue pigeon - a stripper of leaded roofs - he was a weasel too lithe and limber for any snare. He knew not the dismal connections to his life when he first spied the tower of St Cornelius, lusting for its rich rooftop harvest of pliant grey metal. But his joy at pending thievery, at the succulent and unattended prize evaporated the moment his padded feet touched the tainted turf. Coldness rose from the ground; anthropomorphic shadows flitted liquidly from tree to tree and whispers of dread intent followed as he slipped through the waist high weeds betwixt the tombs. In the ground, something stirred. Not often did it wake in these days, some half a century beyond its birth. It had struck, time and again and true to the words of its creator; few now lived that might suffer Speighthart’s power, but still it lived on.

With a crash of worm-bit timbers, the would-be thief fell through the roof of the church and lay agonised, his broken bones amongst the broken beams and pews. There he rested, staring helpless to the heavens through the hole he had made and there he stayed until he died, for none could hear his cries. Rat fodder was his fate, and their scampering feet were the last things he heard…that and a ghostly gloating chuckle.

Fifty more years pass and Percy Minchin’s bones are found when the church roof finally fails with a crash, and surveyors come to make the building safe. In the ground, nothing stirs, for no cursed descendants enter the overgrown ruin. Fifty more years again sees the vicarage brought back from the verge of death. The town is now much enlarged, it has engulfed its neighbouring hamlets, and commuters, in turn, invade every spare scrap of space with their modern homes.

But wait…what is this? Who do we see arriving at the newly restored gates of the vicarage? By chance so remote one could scarce believe it could be chance at all, a young family alight their vehicle, and stand, as one, before their new home. The two boys, one twelve, one eight, tear themselves from their parents’ side to run and explore the garden while Mr. and Mrs. Speightart smile proudly and a lorry disgorges their furniture to fill the Victorian pile.

The hands on the clock of time spin backwards and all is a blur until, with a start, we are once more besides the open grave of the Reverend as his coffin is lowered down. Who is this? At the corner? Peeping from behind the coat tails of his guardian’s morning suit? It is Octavius Speighthart! Orphaned and cruelly refused nephew of the departed priest, last of his line, his heir and a ward of court. It is the great great grandson, Markus, who now stands before the renovated vicarage. Some lawyerly oversight of record keeping kept hidden from the Speighthart family the fact that the vicarage was not possession of the Church - which presumption would usually hold true – it was Speighthart’s own full freehold. From within a long-lost strong box, vellum deeds confirmed the inheritance and the neogothic vicarage is once more vested in the bloodline.

The two boys invade the garden. They explore the roofless ruin of Mungo’s cottage, deciding that a witch must surely once have lived there. A game of hide and seek is proposed, and the older boy, as always, goes first.

“It’s the rules, Steven,” he says, “The oldest always goes first, and I’m the oldest.”

“It’s not fair!” - the common cry of the younger boy – “You’ll always be the oldest and I’ll always be last!”

The older brother isn’t listening; he’s off to hide and shouts back “Count to one hundred and no looking!”

Steven stumps sullenly, counting out loud as he bashes at walls with a worn spade handle he has found. He bemoans his lot, as the youngest, the one that always goes last. A breeze picks up and the sound of hissing leaves breaks his concentration. He forgets the count and steps outside the house to look up into the trees which bend in the wind and creak to each other. Then another sound turns his head - a metallic sound, intermittent but clear, chiming just slightly beneath the rustle and sway of the trees. As he approaches a high wall, the chiming sound becomes clearer still. He scals it easily, for dark roots have burst through the stones here and there, and soon he is up and over and beyond into the churchyard.

The source of the chiming is revealed – a weathered brass bell which dangles on its mounting, fixed to a moss crusted gravestone. He pokes at it with a stick and it chimes again. He hits it harder and harder, with each stroke causing a louder peel to ring out – a delightful game! Setting his feet, and swinging back his stick, Steven hits the bell as hard as he possibly can, for that’s what any young boy would do, but the stick breaks and the bell bracket gives way under this last blow. One final chime rings out and the bell falls to the ground, the clapper silenced and muffled. Crestfallen that his game is over, Steven scrabbles in the weeds to claim the bell as trophy at least, and bending to the dirt, his eyes fall level with the writing on the stone. It is not quite legible, but with some scraping away of moss, letter by letter he spells out what is revealed:

“S…P…E…I…. Speighthart!”

He speaks the word, his own name, and all falls silent in the churchyard. The wind stops, no bird sings. There is not a sound, for a heartbeat, for another and another still and then all begins again as if the world held its breath for that moment. Beneath the ground, something old and bitter stirs into wakefulness.

to be continued…Here

I must learn not to read these in the bright birdsong mornings. I’ll try to save the next episode for middle of the night owl cry darkness…

Oh this is so damn good, Nick. It’s so rich with detail. My parents live in a rural village in England and I live in a very rural hamlet in Wales. Tales like these run riot in the dark nights!