The Legacy: Part I

I was aiming to submit this to a sinister Christmas collection but fear I may be unable to complete it afore the year be out...but here is the first part...

The Reverend Severin Speighthart was not a well-loved man. Heart cold as the stone of his church, his stare was baleful from the black pulpit whence flew his withering condemnations. His back was as stiff as his silver-topped stave and his voice was riven with a harsh hint of the raven in its judgements.

What evils did our forefathers undertake to bring us such ungodly punishment as this priest? the townsfolk wondered. Sunday sermons were a torment, for who knew where the accusing finger of damnation would point? Weddings were sapped of their joy as bride and groom were reminded that death would surely part them, and perhaps soon. Funerals were suffused with his barely contained glee as a litany of exaggerated sins were recounted and the departed sent on their way, assuredly to a fiery eternity far from the bosom of the Lord. Babes were baptised under a shadow of implied bastardy and into the certain sinful care of parents unfit to guide them in godly ways.

And so it was almost audible, when the town learned of his demise, the collective sigh of relief when the Reverend left their mortal coil. Mungo the gravedigger bore witness to his passing one stormy day and at close quarters, from six feet down in the ground, as he made the grave for a Mrs. Gwendoline Golightly, thrice a widow. Many, and by many, were the times he was entreated to recount the matter and spare no detail for their hungry ears.

“Eighty eight inches, Mungo! Eighty eight and no fewer! Your victuals and your two shillings will wait until you have dug it thus.” The stick-thin Reverend shouted down at at the toiling man.

Mungo looked up from the pit. “’Tis a full six feet, Reverend. I knows my trade and a foot beyond my nose this hole be,” he said, pressing his snub and lumpy nose into the clay of the grave side to prove it. The Reverend thrust his skull-topped stave into the hole and a clear foot stood up beyond the grass.

“Six feet of God’s dirt must cover the doomed, Mungo! Six feet under must they be and not an inch less! This black rod of mine is made precise for this good purpose, Mungo. Six feet of dirt above and one and one-half feet below for the casket in which the pitiful sinners rest. Listen! Do you not hear the bones of Mrs Golightly, the bed-hopping harridan, shivering within her box afore the alter whilst her corpse awaits the reckoning? Doubtless the Lord’s judgement shall be one more justly harsh than any I shall muster at her funeral service. Foul slattern! Widow’s weeds for barely a year before she leapt like a spring heeled harlot to the next coin purse, then shameless came to me each time to bless the union! She must feel the full weight of the pit pressing upon her! Dig! Dig on man, and deeper until the skull atop my stave is down there too!”

At this, the Reverend had raised his staff into the air, brandishing it as if to challenge the heavens and call down judgement from above on the departed lady. In truth, in life, Gwendoline Golightly (formerly Smallbones nee Rowbottom) was a charitable and pious woman, much loved, handsome and radiant, friend to many. Nether Clevehaven was a town far from the sea and no stranger to cholera nor to many other means by which men could be took, long before their three score years and ten. And so Gwendoline was three times made a widow before her own time came. She was thoroughly undeserving of the Reverend’s bile, so when the judgment came, it was a righteous one indeed. A lightning bolt broke open the skies with a crack, the silver topped stave was struck and the Reverend sent toppling into the fresh hole, silenced at last.

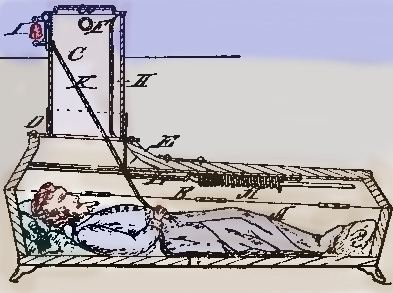

It was perhaps the swiftest funeral that had ever been arranged. A grave was dug as far from the church as possible, shadowed by Mephistopheles the twisted yew, and practically touching the graveyard wall. Men queued to help Mungo dig it an extra foot deep for good measure. Families almost came to quarrels of politeness to give up their order at the undertakers and make free a casket there and then; the same was true at the stonemasons for his tombstone. The townsfolk wanted him under the ground as fast as decency could allow, lest the lord change his mind and there was but one concession to their haste: the Reverend’s will had specified that his grave be fitted with a Taberger’s patented safety coffin bell. None wished to risk spiting the man – a man of the cloth, after all – by denying his testamentary wishes, and so the device was fitted. A rust resistant brass bell was connected by brackets to the grave slab, with a chain descending by means of a brass tube through the earth and into the hands of the coffin’s occupant, thereby affording a means of rescue, should their death be mispronounced.

The whole town turned out for this funeral. The Vicar of Sodworthy under Nettleburn was brought, post haste, by carriage to deliver the service and not a word of eulogy was written for him to read. If thou hast nought good to say, then say thee nought, it is said, but mutters of Amen rumbled around the grave as the first handful of soil drummed upon the lid. Louder still “AMEN!” from one and all when the hole was filled back up to the brim and Mungo beat it flat with six mighty blows of his spade, as if to say Get thee down and stay there!

The throng stood in silence for some time, half expecting, nay fearing, that the brass bell might chime, that the Reverend might somehow cheat Death himself from his harvest, just as the Reverend had wrestled the joy from all their lives. Never had so many silent prayers been offered up for a man to truly be dead and gone and taken to the lord, or elsewhere. A full ten minutes it was before the first of the watchers felt sure enough to leave and file out through the wychegate. Eventually, the grey granite tombstone engraved with a single word “SPEIGHTHART” was all that stood in attendance.

That evening, as dusk fell, Mungo tramped to the Reverend’s grave, casting glances round and about to make sure he wasn’t seen.

“I am but the gravedigger,” he said to the mound of earth, ”but I knows what is holy and good and right, and I knows what ‘aint. I have seen you, Reverend, seen you send my kin and neighbours on their way with undeserved curses and foul judgements to a man. Not one has escaped your ire – not so much as a single innocent babe! But now your time is come and I trust the good Lord to judge you fair, for my judgement here counts for nothing next to that reckoning.” He bent down close to the gravestone and spoke into the brass pipe down which the bell chain hung.

“Your last testament decreed this here bell be fitted…but nowhere was it written that the chain to it be not broken.”

And with that he brought out his tin snips and cut the chain. With a hiss, the brass links whispered into the depths. “Eighty eight inches just as you like it, Reverend, and a good few more besides. Rest thee well.”

to be continued…within Part II…

Oh wow, this is fantastic. It reads just like an old legend (as I assume you intended). And that description of Reverend Severin Speighthart... "His back was as stiff as his silver-topped stave and his voice was riven with a harsh hint of the raven..." We know exactly who we're reading about! I'm looking forward to the rest of it.

I really enjoyed the drama and humor here! As much as I love redemption stories and anti-heroes, it's nice to see a story start with a bad guy who is (at least for the moment) a straight-up bad guy!